It is monsoon season in Bangladesh and humidity is high. The annual seasonal increase of illnesses such as dengue and Chikungunya is in full swing, and many patients are presenting with high fevers and chills.

Nur Begum is with her daughter who is waiting to be seen at Jamtoli clinic in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. They sit on the wooden benches from early in the morning, sheltered by the bamboo roof, and health promoters take the opportunity to share awareness messages whilst they wait. Some women lie down, their heads resting on their handbags or even their umbrellas, their children’s tired arms draped over them.

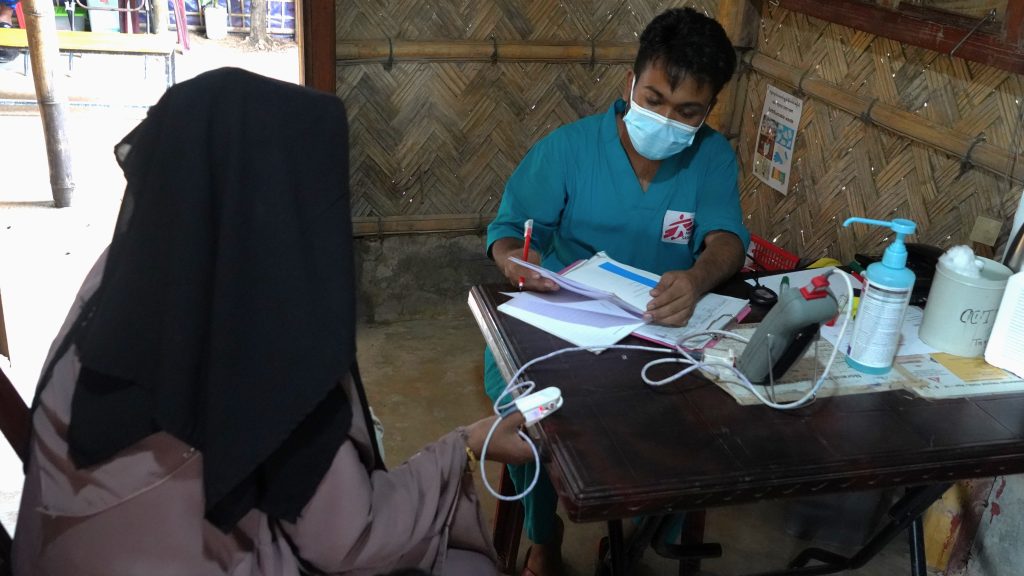

“There are seasonal increases, but what we’re also seeing is higher numbers of patients with non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes. We used to get two or three of these cases every month and now we’re seeing ten to 15,” explains Dr Abdur Rahman, who works in MSF’s Jamtoli clinic. “We have a maximum number of people we can start on treatment for non-communicable diseases every month to ensure we don’t run out of drugs or put too high a strain on our staff. Once the number of patients exceeds the amount we can treat without compromising quality of care, we try and refer new patients to other health facilities for treatment, but it’s a challenge”.

The number of people coming to the MSF emergency rooms in camps 14 and 15 in June 2025 was 140 percent higher than early this year. Some patients arrive very early in the morning and wait for hours, others come at night when the queues are shorter. “There used to be 30 to 40 patients at night, now there are often more than 100,” explains Amir Hamza, one of the triage nurses. The outpatient departments are also working over capacity.

To reduce the waiting times, and some of the pressure on the facilities and on the staff, MSF has decided to focus on those more seriously or critically ill. But this has understandably led to frustration, especially as several health facilities run by other organisations have had to reduce services, meaning there are fewer options for care. Due to reduced funding, the impact is likely to grow even more significant in the future; the Rohingya crisis has become a protracted one and conflicts and crises have broken out or worsened elsewhere in the world.

Over one million people live in the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, some for decades but many since the deadly crackdown in 2017 that sent hundreds of thousands across the border from Myanmar to Bangladesh. The fighting in Myanmar continues today and the camps have seen a significant rise in new arrivals since last year, putting even more pressure on what little assistance is available. “One of my sons moved to us from Myanmar with his eight family members three months ago. So far, he hasn’t received any rations. It is becoming difficult for us to feed so many people,” says Abdul Kalam who comes to MSF for his diabetes medication.

After a few hours Nur steps out under the gathering rain clouds, avoiding the puddles on the red brick path, to get some air. “My daughter has a high fever; her body is shivering, and she feels cold and so we came to the clinic. Sometimes though I know I will have to wait for a long time, so I don’t come at all”

In Cox’s Bazar, MSF manages ten hospitals and primary health centres. MSF activities cover a range of inpatient and outpatient services, including emergency and intensive care, paediatrics, obstetrics, sexual and reproductive healthcare, treatment for survivors of sexual violence and patients with non-communicable diseases.